“Hindutva,” as both term and concept, is usually identified with VD Savarkar (1883-1966). His 1923 essay, originally titled, “Essentials of Hindutva” and retitled, “Hindutva: Who is a Hindu” in its 1928 reprint is the most frequently, often the only, cited text in this regard. Even the ever-popular Wikipedia has it wrong in saying that the word was “coined in the early 20th century.” A respected commentator from the right, offering a corrective to such views, wrote a recent article on how “the Hindu nationalist tradition is not alien to West Bengal.”

He is absolutely right. Like most modern ideas in India, “Hindutva,” too, was born in Bengal in the 19th century. But even he fails to mention its probable progenitor. A Bangla tract by that name was published in 1892 by a bhadralok man of letters we have forgotten today. His name is Chandranath Basu (1844-1910). Like many other leading figures of that time, he too studied at the Presidency College, getting a BA in 1865. Hoping to make a lucrative career in law, he also picked up a BL degree a couple of years later. However, he never practised law. He worked for a while in the education department, before being appointed as Deputy Magistrate, like Bankim Chandra Chattopadyaya, the leading literary figure of the times. But that didn’t suit Chandranath either. He returned to education, becoming the Principal of Jaipur College, Calcutta. After a while, he worked for the Bengal (later National) Library, finally being appointed as a translator in the Bengal Government in 1887. Though this may not seem like such an illustrious career move today, in those days it was a Class I officer’s post and quite important to the colonial regime. Chandranath occupied it till his retirement from service in 1904.

Chandranath’s forte, however, was literature. He started, as many young aspirants of his time, in English. He even founded a monthly called Calcutta University Magazine. It was Bankim who urged him to switch to Bangla as he himself had done after his own false start, Rajmohan’s Wife (1864), an incomplete, some say, first Indian novel in English. Chandranath began to publish in Bangadarshan, Bankim’s journal, the preeminent literary periodical of the day. He soon made a name for himself, publishing in other leading magazines including Girish Chandra Ghosh’s Bengalee, Akshaychandra’s Nabajiban, and so on. Rabindranath Tagore knew him well and mentions him in his reminiscences. An index of his importance is his election as the Vice chairman of the Bangia Sahitya Parishad in 1896 and Chairman in 1897. Earlier incumbents included its founding Chairman, Romesh Chandra Dutta (1848-1909), ICS, economic historian, and translator of the Ramayana and Mahabharata into English verse. Tagore himself had served as the co-Vice-Chairman of the Parishad with Nabinchandra Sen.

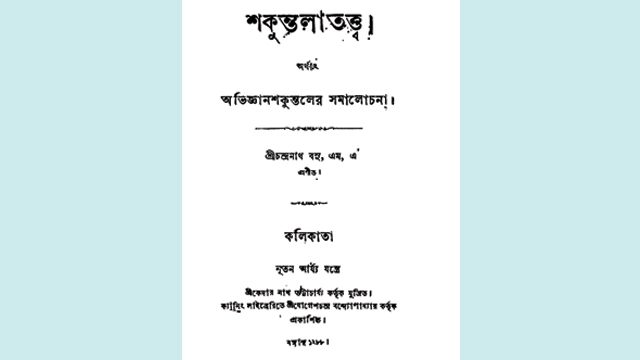

Chandranath wrote several books including Shakuntala Tattva (1881). Note his use of “tattva” (reality or essence), long before he used it to coin “Hindutva.” The rediscovery and translation of Kalidas’ Shakuntala in 1789 led to a lively discussion of its greatness among the Bangla intelligentsia. Kalidas’s play became central to the conceptualisation of a modern Indian aesthetic tradition. Not only Chandranath, but Tagore also wrote on this key text. Later, Acharya Hazariprasad Dwivedi would also discuss Chandranath’s Shakuntala Tattva. Chandranath went on to write a historical novel, Pashupati Sambad (1884), a critical survey of the newly emergent Bangla literature, a product of the Renaissance in which he himself was an important actor, Bartaman Babgala Sahityer Prokriti (1899), and several other books, some of which also tried to define Hindu traditions and practices. Of these, the most important, of course, was Hindutva (1892). He was to resort to the same principle of going to the fundamentals (tattva) in his last major book, Savitri Tattva (1901) too.

Unfortunately, no one I know has read Chandranath’s Hindutva. Though it is referred to in several scholarly studies of 19th century Hindu reform movements, not a single scholar offers a detailed study or analysis. It is neither available in English translation nor, it would seem, easy to get in Bangla. The longest reference to it in English that I could find was in this “Critical Notice” in the Calcutta Review of July 1894:

“Babu Chandra Nath’s is the first work which treats of the Hindu articles of faith. It aims at being an exposition of the deepest and abstrusest doctrines of Hinduism, not in a spirit of apology, not in a spirit of bombast, but in a calm and dispassionate spirit. The work is a difficult one. The Hindus are notorious for the diversity of their transcendental doctrines, every individual school having a complete set of doctrines of its own. Babu Chandra Nath has selected the noblest doctrines of Hinduism, but he has not followed any one of the ancient schools. Yet he does not aim at establishing a school of doctrine himself. His sole object is to compare, so far as lies in his power, the leading doctrines of Hindu faith with those of other of other religions.”

I have quoted at length to show how such a comment certainly whets, but satisfies neither our intellectual curiosity nor scholarly appetite.

I have often argued, as in my book Making India (2015), that the 19th century offers the key to our understanding of what transpired afterwards, how we ended up becoming what we are today. With the renewed interest in the pre-history of Hindutva, I hope some institution or scholar will assume the much-needed commission of republishing Chandranath’s pioneering treatise. It will be one more step in the direction of creating an alternative narrative of recent Indian history.

By Makarand R Paranjpe

The author is a poet and Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.