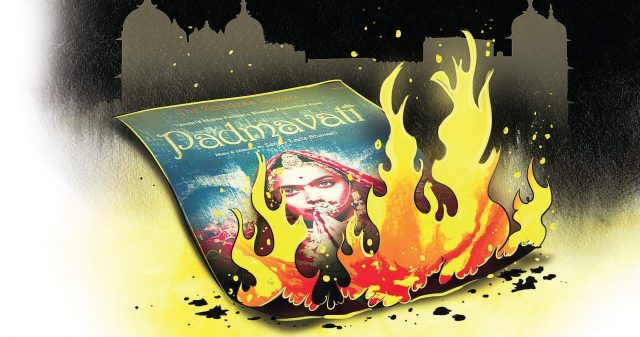

On the face of it, there can be no logic to the mass hysteria one is witnessing today over Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s film Padmavati. By their own admission, not one of the protestors has seen the film, but lakhs of people belonging to the Rajput community in particular and to other Hindu castes in major states in the North have come out onto the streets demanding the film be banned. While some protestors have publicly shared their concerns, most have not.

But the central fear it appears is that Bhansali may have shown Padmini alias Padmavati as responding to Alauddin Khilji’s advances resulting in some romantic scenes on screen—something that would be considered abhorrent and blasphemous by the Hindus.

Some media professionals, who watched a special screening of Padmavati, have tried to douse the flames by claiming that these rumours are baseless and that the two characters in the film—Padmavati and Khilji do not ever come together. Yet, the protests continue and some are even attributing this controversy to the upcoming elections in two states.

This seems a bit far-fetched. Instead, the frenzy and the irrational responses of the protestors can be traced to the deep distrust among the Hindu majority over the “history” of India, especially medieval history, written by pseudo-secular, Nehruvian and Marxist historians.

For long years many of these fabrications, like discovering the “secular” credentials in Aurangzeb, a despot who plundered the holiest of Hindu shrines and inflicted untold cruelty on the Hindu population, had gone unchallenged. For decades after Independence, there was a kind of lethargic acceptance by the people of this intellectual dishonesty, although through the oral history tradition, they were always aware of the truth.

Since the Nehruvians and Marxists constituted the “Establishment” in New Delhi until circa 2014, their pernicious influence has extended to literature, cinema, etc. This emboldened many artists like filmmakers and painters (M F Husain) to take their right to freedom of expression to absurd levels of Hindu-bashing.

But now a mass awakening is happening. This can be attributed to two reasons. Firstly, people have started questioning these fallacies because popular forms of art like cinema have begun to spread them. Secondly, despite the shenanigans of wily left-wing conspirators in academia, we have a band of historians who have tried to demolish such fantasies and bring history closer to the truth.

Some of these historians from R C Majumdar to Prof K S Lal, Dr S P Gupta, Prof Makkhan Lal and Prof B B Lal have challenged the narrative in regard to both ancient and medieval history. This course correction is currently on in the current phase of our national life and the exaggerated fears about Padmavati, the movie, is part of this process.

Coming back to Alauddin Khilji, it is said that he set out from Delhi for Chittor on 8 January 1303. He laid siege to the Chittorgarh fort later that year. According to historian Dasharatha Sharma, who has chronicled Rajput history and culture, Khilji set up camp between the Berach and Gambhiri rivers.

On August 26, Raja Ratna Singh decided to throw in the towel, but his people decided to fight on for some more time “with the result that when the fort passed into the hands of Khalji emperor, 30,000 Hindus were put to the sword in one day” and the beautiful Padmavati and her companions “threw themselves into the fires of Jauhar” (and immolated themselves). Sharma quotes Malik Muhammad Jayasi, who wrote his allegorical poem Padmavat in the year 1540, as saying that “eventually all that Alauddin secured of the lady he had desired to possess was barely two handfuls of ashes”.

Many historians base their judgement on Jayasi’s poem. Sharma says perhaps no heroine of Rajasthan has attracted greater attention of poets and writers than Padmavati. He sums up the folklore about Rani Padmavati when he says it has assumed various forms but the central figure of all these accounts has always been the same: “The brave, beautiful and indomitable Padmavati, who could befool a lustful tyrant and also fearlessly—almost joyfully one might say—consign her body to the fires of Jauhar when honour so demanded”.

The Rajputs and other Hindu castes regard Padmavati’s decision to commit Jauhar rather than fall into Khilji’s hands as an act of valour which upholds the honour and dignity of all Indian women. As a result, Padmavati enjoys the status of a “Devi” in the minds of the people.

The exaggerated anxieties of the Rajputs can be traced to their fear that Bollywood is out to distort the bold and the beautiful image of Padmavati. Also, many people believe Padmavati existed and she upheld values dearest to a Bharatiya Nari. Yet, in the midst of this controversy we have some eminent left-wing “rationalists” not only questioning these beliefs but even mocking Hindus for their reverence for what they claim is a fictional character.

Bollywood must guard against such foolhardy intellectual troublemakers who frequently challenge Hindu beliefs and opinions. Once the source of the problem is identified, it should be easy for Team Bhansali to douse the fires. But why did Bhansali make no effort to nip this controversy in the bud if the feared “distortions” are not there in his film? Bollywood will be able to avoid such confrontations with sections of the people if it stays miles away from such intellectual troublemakers.

Meanwhile, despite all this controversy, it is the duty of the Indian state to ensure that Bhansali’s fundamental right to freedom of expression is protected and those holding out murderous threats to the film’s director and the actors are dealt with firmly under the law.

A Surya Prakash

Former Chairman, Prasar Bharati

Courtesy: The New Indian Express