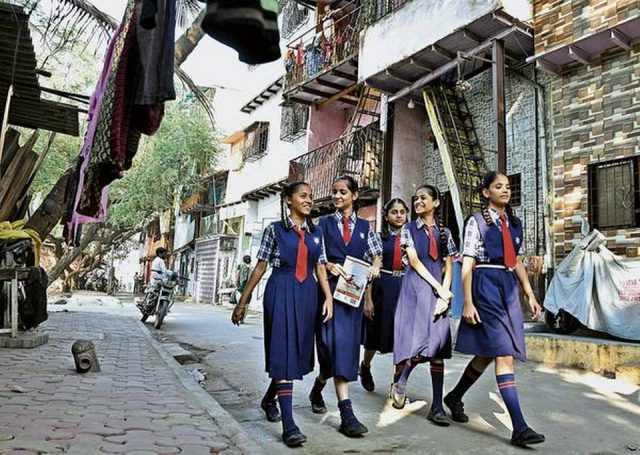

An inspired group of Class VI students leads Project Balika to get underprivileged girls back to school

Two years ago, Nida Shaikh, Shifa Qureshi, Kusum Chaudhry, Anu Kumavat, and Pooja Doddi, classmates and close friends, were very disturbed. Their friend Bushira Shaikh was quitting school.

This was not unusual in Holy Mother School, where they were all students of Class VI. The school sits in a low-income, high-density slum area in Malwani, a Mumbai suburb, and many other girls had quit school because of the lack of family support. And not unusually, Ms. Bushira’s family couldn’t afford the fees.

But her friends decided this was no reason for her to quit. The five went around the community, collecting money, and soon Ms. Bushira was back in school.

Crusading spirit

Inspired by their success, the girls decided they would now get others also back to school. They went door-to-door, talking to parents about the importance of sending girls to school and collecting money to pay fees for those who couldn’t afford it. “Some parents listened patiently,” Ms. Nida says. “But most of them refused to be convinced. We were unable to collect much funds either.”

Come 2016, the girls found a new ally when Jasmine Bala joined their school as a Teach for India (TFI) Fellow. Ms. Bala was impressed by their comittment.

“They wanted to be changemakers in their communities and make a positive impact,” she says. “These girls are critical thinkers and are aware of the issues in their community, the foremost being the suppression of young girls. There is a high drop-out rate of girls from secondary classrooms.” Another challenge is the high incidence of alcoholism, drug abuse and abuse of girl children in the area, Ms. Bala says. “We wanted to instil confidence and help them step out of their homes without compromising their safety,” she adds.

Ms. Bala helped the group get more organised. And this year the girls, all aged between 12 and 14, started Project Balika.

Firsthand experience

The initial focus of Project Balika was to convince families of the importance of education for girls. But this was not easy. Parents often refused to listen, firm in their belief that a girl’s goal must be to marry and raise a family. Hence, learning household chores was considered more important. The project’s founders knew this first-hand. Ms. Kusum, who scored 92% in Class VII and excels in English, says, “My father too does not want me to pursue higher education, though I am good in academics.”

Thanks to their refusal to accept the status quo, the five trailblazers inspired many more to join their effort. Balika’s group of changemakers has now grown to 40, and they have impacted more than 200 young girls and women in Malwani. They want to take that number to 500 next year.

The project now runs a number of activities aimed at empowering girls to take up leadership positions, tackling issues of gender discrimination, safety of girls in the community, and improving health. “All the work, from coordinating with government officials to meeting with headmasters of schools to working with various community members, is done by us,” says Ms. Shifa proudly.

Balika also runs free English-speaking classes twice a week for young mothers and school dropouts.

“I have been teaching English to eight mothers for a month,” says Mahek Bilal, 20. “I have started with alphabets, as they had never studied English before.”

Shama Shaikh, 34, who joined the class last week, is ecstatic: “I was good at stud- ies and dreamt of becoming a teacher, but I was unable to continue after Class VIII because of family pressre and financial constraints. Now, if I learn English, I can help my kids with their studies. And if given an opportunity, I may even seek a job!”

Yasmin Khan, 30, from a small village near Lucknow, also had to drop out of school after Class VIII, when her family arranged her marriage and she moved to Mumbai to join her husband. “After marriage, I never got an opportunity to re-join classes. By learning English, I can at least give home tuitions and earn for the family,” she says.

Going beyond academics Ms. Anu says, “We spread awareness on menstrual health, nutrition and safety of girls around schools in Malwani.” The project members want to install a vending machine in their school to enable girls to get subsidised sanitary pads.

So far, Balika’s funds have come from individual donations, but Ms. Bala hopes they can access Corporate Social Responsibility funds as well. This will help the programme expand to other repressed communities in Mumbai, she says.

Monthly review

To track the leadership journey of each girl, Ms. Bala holds a monthly meet where high-performing girls work with female mentors. “Currently, there are 50 mentors who work with the children and check their progress.” The teaching isn’t one-way, though. “The girls have been invited to deliver lectures to first and second year students at the Narsee Monjee and Government Law College on the importance of student leadership and performance management trackers for leadership development.”

Looking back, Ms. Pooja says that she is happy they have helped so many girls re-enrol. But, she adds, “I really wish Balika can convince every parent to send their daughter to school so they can have careers of their choice.” Her personal plan? Apply for a TFI fellowship and become a teacher like Jasmine Didi. “And then, run an education NGO!”

By Vardha Sharma

Follow Malwani’s changemakers on Facebook.com/projectbalika

Courtesy: The Hindu