In November –December 2014 there was an election for the Legislative Assembly of the state of Jammu & Kashmir and the state is now under a coalition government run by PDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) and BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party). Leh and Kargil seats were won by Indian National Congress whereas the Zanskar seat located in the south-eastern part of Kargil district was won by an Independent. For the first time, BJP is part of the ruling dispensation in J&K although it has failed to win the Buddhist majority seats of Leh and Zanskar.

Since then several unsettling events have taken place; first, the tallest leader of PDP and Chief Minister, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed died; then there was the death of the most dreaded terrorist Burhan Wani in an encounter with the security forces; it was followed by a stone-pelting protests in which many were killed and many more injured, both among the protestors and security forces. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Narendra Modi raised the bar against Pakistan by expressing concern for human rights violation in Baluchistan and Gilgit-Baltistan (the so-called Northern areas of J & K) and extending moral support for the on-going peoples’ struggles there against Pakistan’s occupation.

Against this backdrop it is expected that BJP would bring in new ideas and usher in new policies in the J & K; for instance, after coming to power in the state, it had lost no time in starting a debate on how to re-settle Kashmiri Pandits who had been hounded out of the valley of Kashmir in 1989-90. Likewise, it is hoped by this author that a new education and language policy will be formulated by the government; a major shift in language policy for the Kargil district of Ladakh is an immediate crying need; for several years successive Kashmir governments have been following a policy of separating Kargil from Buddhist-majority Ladakh and bringing it under Kashmir, not by direct legislation but by stealth; a new language policy, backed by political action, would prevent that, it is hoped.

Further, the new policy proposed here would give India room for geopolitical manoeuvres vis-à- vis Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir. In order to make a case the arguments must be presented in a proper historical context.

In India, we usually call the Pakistan occupied part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir as POK or Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. Likewise, in this article, we shall call the part of Ladakh disputed between India and China as COL (China-occupied- Ladakh). Baltistan is that part of PoK that is contiguous with the Kargil region of northwestern Ladakh. In turn, the north-eastern part of Ladakh is contiguous with the western Tibetan plateau. Baltistan is disputed between Pakistan & India, and western Tibetan plateau between India & China.

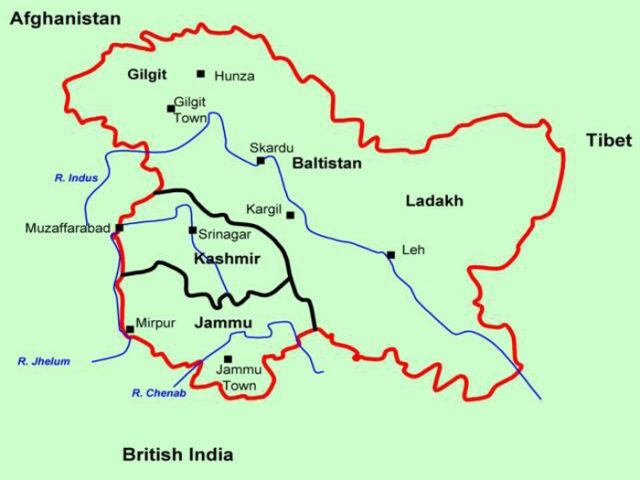

Baltistan, Leh-Kargil part of Ladakh and western Tibetan plateau are now under the control of three different countries, but peoples of these three regions are of the same race and speak the same language. It is not well known in the rest of India that Baltistan was a part of Ladakh district before 1947. Fig. 1 shows a map of the eastern part of the J & K state in which these three regions can be seen.

The original Ladakh district, as it was before 1947, is shown by a double line boundary. The Line of Control (LoC) is depicted by a chain of dots. The approximate map of 35-year-old Kargil district is shown south of Baltistan separated by the LoC. The town of Skardu that lies north-west of Kargil town across the LoC is the capital of Baltistan. The Karakoram highway being constructed by China to connect Western China to the Arabian sea via the Gwadar port is shown in Fig.1, but its location and orientation in the map is only notional & symbolic, and far from exact.

It must be mentioned that the western border with Tibet had never been demarcated on the ground before or after 1947 and the present line of control is also fluid and contested between India and China while the territory of Aksai Chin is now under China’s control.

The inhabitants of Baltistan are called Balti who call their land by a Tibetan name Baltiyul which is derived from the original Tibetan script called Balti that was prevalent in the area before Islamization (to Shia faith) took place in the 16th century during the reign of king Ghota-Cho-Senge. Islamization took place late in these parts, about three centuries later than in Kashmir valley. Thereafter the Arabic Nasq script was introduced. A Buddhist minority exists even now in Baltistan of PoK, although very thin on the ground. The part of Ladakh district that came to India has in its north-western part, around the town of Kargil, a Shia Muslim majority. As one moves in the south-easterly direction the Buddhist population increases and in Zanskar and Leh they become a majority.

Buddhists of Ladakh retained the traditional script called Bodhi (alternatively, Ladakhi) and they call their language Ladakhi. Tibetan language, all over present Tibet, is written traditionally in an alphabet that bears resemblance to Devanagari and Bengali. So it is evident that Bodhi script of Ladakh is of Indian origin. The Nasq (Arabic) script became popular with Muslims, and since it came to India via Persia, it is often called Persian script. The language written in Nasq is called Balti. However, spoken Ladakhi and spoken Balti are the same languages. In a sense, the relationship between Nasq-Balti and Bodhi-Ladakhi is similar to that between Nasq-Urdu and Devanagari-Hindi.

Initially, the sparsely populated Ladakh region consisted of a single district called Ladakh (as shown in Fig. 1) with its capital at Leh. When Sheikh Abdullah was brought out of imprisonment and reinstated as the Chief Minister in the latter half of the 1970s, he created a few new districts and sub-divisions along communal lines in different parts of the state. A Muslim-majority sub-division called Gool was carved out of composite Reasi sub-division in Jammu region and Ladakh district was bifurcated into Muslim-majority Kargil and Buddhist-majority Leh. Further, Buddhist-majority Zanskar subdivision was mischievously included in Kargil district instead of in Leh district. So now there remains no district called Ladakh, which was the original name. However, the whole composite region is still called Ladakh, as before, and that has significant legal implications.

Language and script

Between Balti and Ladakhi all verbs and 90 percent of words are in common (Kazmi 1996). The following tables from Kazmi (1996) give an illustrative sample.

| Balti Words |

Ladakhi |

English |

| mGo |

mGo |

Head |

| Mik |

Mig |

Eye |

| Laqpa |

Lagpa |

Hand/Arm |

| Khap |

Khap |

Needle |

| Skutpa |

Skutpa |

Thread |

| Karfo |

Karpo |

White |

| Naqpo |

Nagpo |

Black |

| Marpho |

Marpo |

Red |

| Shing |

Shing |

Wood/Timber |

| Chu |

Chu |

Water |

| Khi |

Khi |

Dog |

| Bila |

Bila |

Cat |

| Kha |

Kha |

Mouth |

| Chharpha |

Chharpha |

Rain |

| Khnam |

Nam |

Sky |

| Sa |

Sa |

Soil/Earth |

| bZo |

Zo |

Cross of Yak and Cow |

| Da |

Da |

Arrow |

| Gju |

Gju |

Bow |

| Kangma |

Kangpa |

Leg/Foot |

| Zermong |

Sermo |

Nail |

| Api |

Api |

Grand-mother/Old Woman |

| Ashe |

Ache |

Elder Sister |

| Bang |

Balang |

Cow |

| Byango |

Chamo |

Hen/Chicken |

| Ong |

Yong |

Come |

| Mendoq |

Metoq |

Flower |

| Nang-Khangma |

Nang-Khangpa |

House (holds) |

| Shoq-shoq |

Shugti |

Paper |

| Garba |

Gra |

Blacksmith |

| Shingkhan |

Shingkan |

Carpenter |

| Bras |

Das |

Rice |

| Bakhmo |

Paghma |

Bride |

| Nene |

Ane |

Aunt |

| Khlang |

Langto |

Bull/Ox |

| Stare |

Stari |

Axe |

| Zorba |

Zora |

Sickle |

| Khshol |

Shol |

Plough |

| Baqphe |

Paghphe |

(Wheat) Floor. |

| Skarchen |

Skarchhen |

Star (large and bright) |

| Namkhor |

Namkhor |

Cloudy |

| Balti Verbs |

Ladakhi |

Meaning |

| Zo |

Zo |

Eat |

| Thung |

Thung |

Drink |

| Ong |

Yong |

Come |

| Zer |

Zer |

Speak/Say |

| Ngid tong |

Nigid tong |

Sleep (go to) |

| Lagpa |

Lagpa |

Hand/Arm |

| Khyang |

Khyorang |

You |

| Balti Sentences |

Ladakhi |

Meaning |

| Diring ngima tronmo yod |

Diring ngima tonmo yod |

The day/sun is warm today. |

| Ringmo thaqpa gnis khyong |

Ringmo thagpa gnis khyong |

Bring two long ropes. |

| Ra lug kun tshwa kher |

Ra lug kun tshwa kher |

Take the goats and sheep. for grazing |

| Zgo karkong kun ma phes |

Zgo karkong kun ma phes |

Don’t open the doors and ventilators |

| Kushu chuli yod na zo |

Kushu chuli yod na zo |

If there is (some) apple and appricot eat (it). |

| Ragi phali yod na khyong |

Ralgri phali yod na khyong |

If there is (any) sword and shield (please) bring them. |

These tables serve to illustrate two important features. Firstly, the languages of Baltistan of POK and Ladakh of India are practically identical and should be classified as two dialects of the same language. They are given two different names because they are written in two different scripts. Kazmi (1996) a citizen of Baltistan (PoK) observes the following on the relationship between Balti and Ladakhi:

“Apparently, Balti is, at the moment, cut off from its sister languages of Ladakh but has 80-90 percent of nouns, pronouns, verbs and other literary and grammatical characters in common. We can, however, term Balti and Bodhi of Ladakh (Ladakhi) as separate dialects, but not separate languages.”

Secondly, they are the world apart from the north Indian languages such as Kashmiri, Urdu, Hindi etc of the Indo-European family. The center of Balti is the Skardu town of PoK and the center of Ladakhi is the Leh town of Ladakh. The Kargil town of Ladakh lies in between geographically. Hence its language too should be somewhere in between Balti and Ladakhi. This implies that the Kargil speech and Leh speech are practically indistinguishable.

It has been mentioned that there is some similarity between the relationship of Urdu and Hindi on one hand and Balti and Ladakhi on the other. Urdu and Hindi are essentially one language written in two different scripts; this is true for Balti and Ladakhi as well. But the similarity ends here. Balti is a geographical variation of Ladakhi and can be called a dialect of Ladakhi, whereas Urdu is not a geographical variation of Hindi and it is spoken/written all over the Hindi heartland by its Muslim people. Thus Urdu cannot be called a dialect of Hindi.

There is another important feature; nouns and adjectives, particularly abstract nouns of Indian origin, mostly Sanskritic, found in Hindi were purged and replaced by Persio-Arabic words to create Urdu (Ref: Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Samskriti ke Char Adhyay). Balti, although written in Nasq script has never been through this kind of religiously motivated purge. As a result, it is much closer to Ladakhi than Urdu is to Hindi.

Education

Traditionally, the Buddhist Gompas taught one son of every family how to read the scriptures. Western education was started first by Moravian Mission in Leh in 1889. The subjects taught were Ladakhi, Urdu, English, Geography, Nature Study, Arithmetic, Geometry and Bible Study. It is to be noted that the mother tongue Ladakhi and two other useful languages were included in the curriculum (Wikipedia).

After Independence, the Jammu and Kashmir government started opening schools that taught the pupils in Urdu medium till age 14 and thereafter switched to English medium. It is obvious that the Jammu and Kashmir government made a deliberate policy of dropping the mother tongue. On the other side of LoC Pakistan government was doing the same thing by imposing Urdu on the Balti-speaking people of the so-called Little Tibet of Baltistan (Kazmi 1996). Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) was started in 1988 that campaigned to shape public opinion for education reform. As a result of their movement, the mother tongue started replacing Urdu as the medium since 1993. The Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) came into existence in 1995 after the concerned act was passed in the Legislative Assembly.

Urdu and the Arabic script have had a long spell since 1947, owing to the language policy of the state government. Hence, it is likely that in Kargil district the script usage has a variation − Arabic (Nasq) in the Muslim-majority north-western parts and Bodhi in Zanskar, the Buddhist-majority south-eastern sub-division. The language is either called Balti or Ladakhi, depending on the script used. Since 2001 a series of steps have been taken, which spells doom for the language of Kargil, and makes separation of Kargil from Ladakh and its merger with Kashmir a distinct possibility

Impending separation of Kargil

Since 2001 the Indian army has been opening Urdu-medium primary schools in Kargil to promote literacy, as a part of its Sadbhavana (meaning goodwill) program (Prem Shankar Jha, Hindustan Times, 2001). Evidently, this was on advice from Jammu and Kashmir government, while the Central government was oblivious and lacked any coherent language policy. It should be noted that SECMOL’s mother-tongue-first policy, which was supported by LAHDC, had been in place for previous 8 years. Yet the Indian army followed a policy that ran counter to SECMOL’s. Why didn’t the army start schools in Balti medium in Kargil? There is only one answer to this question.

There is an all-pervasive language ideology permeating the Central government, Jammu and Kashmir Government and the Indian Army. It says, ‘Urdu is the language of the Muslim’. This ideology plays into the hands of those forces which wish to separate Kargil from Ladakh and join it to Kashmir. Balti/Ladakhi being of Tibetan family is as far from Urdu as chalk is from cheese. Verbs, pronouns, nouns, adjectives are all different. The uninformed and short-sighted move of General Arjun Ray has interrupted a linguistic continuity from Baltistan of POK to Ladakh of India to western Tibetan plateau. In fact imposition of Urdu on Kargil is bound to affect the morale of Balti people in POK who are struggling against Urdu imposition themselves (Kazmi 1996). And it is likely to demoralize people of Leh who are trying to earn a place for their language in the state of Jammu and Kashmir and who too may be the next victim of Urdu hegemony.

Ironically, Pakistan is also an adherent of this ideology and had tried to impose Urdu on Bengali Muslims of erstwhile East Pakistan, leading to break-up of Pakistan and creation of Bangladesh. Pakistan has also been trying to impose Urdu on the people of Baltistan and suppress their mother tongue. The irony becomes doubly sharp when the Indian army does the same on the hapless people of Kargil. Lately, there are signs of language-based re-awakening in both Baltistan and Kargil. More about it later.

The political phase of separating Kargil started when the PDP-Congress coalition came into power in Jammu and Kashmir in 2002. The Common Minimum Programme (CPM) of the coalition said (Hindu 2002):

“The government shall grant full powers to the Autonomous Hill Council for Leh, which has hitherto been deprived of its legitimate powers. Efforts will be made to persuade the people of Kargil to accept a similar Autonomous Hill Council for Kargil.”

When the CMP was written, there was no Autonomous Hill Council for Leh. There was only the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC). Why did the two parties use this mischievous and deceitful language? What was the ulterior motive? There is only one conclusion that can be drawn. Both Congress and PDP were conspiring politically to separate the Muslim-majority Kargil from Buddhist-majority Ladakh. It is noteworthy that there was no demand for a separate council from the people of Kargil.

Even then, a separate council was being foisted on them from above. The intention was to create a religio-linguistic-political division where only a religious difference with strong syncretic and even marital links between Buddhists and Muslims existed. This action of the Congress is comparable to its political move in Kerala in the 1950s and 1960s, whereby the ban on the Muslim League was removed, a coalition government with it was formed and eventually a Muslim-majority district of Malappuram was created.

The promise of the CMP was fulfilled in July 2003 when the coalition Government formed the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council for Kargil (LAHDC for Kargil). A strange name indeed! It formed also the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council for Leh (LAHDC for Leh). Why such strange and tortuous names? If we call ‘Kanpur Development Authority’ by the name ‘Uttar Pradesh Development Authority for Kanpur’, it would be considered absurd.

According to a bill passed in Jammu and Kashmir Assembly an autonomous council is legally valid only for Ladakh. Hence, an entity called ‘Autonomous Development Council for Kargil’ would be legally invalid. This explains the ridiculous contortions in nomenclature which seems legally valid on the surface, but may not actually be so (it should have been challenged in a court), and at the same time serves the purpose of separation of Kargil. The sad thing is no opposition party, not even BJP, challenged these deft moves. The religion-based division of Ladakh has been extended to a sub-division of Kargil; only three council seats out of 30 have been allocated to the overwhelmingly Buddhist Zanskar subdivision. The aggrieved people of Zanskar, both Buddhists, and Muslims, boycotted the July 2003 election to LAHDC-for-Kargil (Hindu 2003). In a speech in New Delhi in 2006 Mehbooba outlined her ideas about self-rule:

“PDP would like the state to be divided into three regions, Leh-Ladakh, Kashmir, and Jammu, each having its own legislature”.

Mehbooba coins a new term ‘Leh-Ladakh’. She is silent on Kargil. The implications are ominous. Presumably, Kargil would be merged with Kashmir under one legislature. It should be noted that as a whole Kargil district of Ladakh has a Muslim majority, although its Zanskar sub-division is predominantly Buddhist. If her intended scenario comes true, then the following is likely to happen:

Leh-Ladakh Assembly will function in Ladakh and Jammu Assembly will function in Dogri or Hindi. Kashmir will continue to be administered in Urdu. It cannot possibly switch over to Kashmiri with Balti-speaking Kargil on tow. So people of Kashmir will once again be deprived of the right to education and administration in Kashmiri, their mother tongue.

It should be remembered that Kashmiris have always described Kashmiri as their mother tongue, and not Urdu, in the census after census. (This should be contrasted with the fact that Muslims of Andhra and Karnataka declare Urdu their mother tongue, although what they speak can at best be called pidgin Urdu and they are more fluent in Telugu and Kannada.

Kashmiri persons of talent, both Hindu, and Muslim, should develop literature and make films in Kashmiri. The script of popular usage Nasq should be the choice so that a literate villager or a common man can read and identify with Kashmiri. All words of common use, whatever may be their origin, should be retained.)

Fortunately, Mehbooba’s idea of trifurcating the state faced stiff opposition from all political parties; and till today J&K is one state and Kargil remains a part of Ladakh. But maps have been printed and distributed, and even reached the internet showing an entity called Leh-Ladakh that is separate from Kargil. And our central government seems blissfully unaware and is unable to connect the dots.

Geopolitics and PoK

The linguistic, educational and historical developments cited here acquire special importance in the backdrop of significant changes in geopolitics in last 5 years. Firstly, the centuries’ old sectarian conflict between Shias and Sunnis have erupted into a continental war of sorts spanning across, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Sunnis of Saudi Arabia and Yemen are locked into a battle with Shia Houtis. Alawite Shia forces led by Assad are fighting ISIS, an extremist outfit of the Sunnis. Iraq is also combating the same organization. Persecution of Shias and bombing their mosques, localities and even buses carrying pilgrims have become a frequent affair in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Even Shias in Kashmir valley are feeling insecure. The original population of Gilgit-Baltistan is entirely Shia. Pakistan has been following a policy of transferring Sunnis from Punjab and NWFP to Gilgit-Baltistan, and this has provoked a backlash. Senge Hasnain Serin, a citizen of Baltistan of PoK and the president of Washington-based ‘Institute of Gilgit Baltistan Studies’, said in Mumbai on 16th April 2015 that there was complete “lawlessness” in the Gilgit-Baltistan, a part of the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, and if a plebiscite were to be held, many people would opt for India.

Secondly, China is building a highway connecting Gwadar port in Baluchistan to Kashgar in Xinjiang province of China, through Gilgit-Baltistan, and has stationed troops and workers in thousands. This also has drawn the ire of the local population.

Third and most important, there is a revivalist movement in Baltistan that seeks to rejuvenate Balti language, overthrow the imposition of Urdu and re-introduce and popularize the use of Bodhi script. To develop the Balti language an intellectual named Yousuf Hussainabadi has taken certain steps. He revisited history and the script of Balti language and revived the Tibetan script in Baltistan after six centuries (1980).

He wrote the book ‘Balti Zabaan’ in 1990 which was the first book on Balti language and translated the Quran into Balti Language (1995). Later many people inspired by Yousuf Hussainabadi started their work on Balti Language. Ghulam Hassan Lobsang wrote two books in Urdu and English “Balti Grammar” and “Balti English Grammar”. The latter was published by Bern University Switzerland in 1995.

A similarly strong movement is underway in the Kargil district too. Zakir Hussain of Balti Education Society for Kargil has been working to popularize Bodhi script, alternatively called Podhi, in primary education. Radhika Gupta (2012) has travelled extensively through Kargil district including remote areas, not usually visited by tourists, and her article gives a fairly comprehensive picture of the ground cultural situation and pride felt by the people in their culture and language of Ladakhi-Tibetan origin.

Conclusion

People of Baltistan (of PoK), Kargil and Leh, all parts of the original Ladakh district, speak the same language but employ two different scripts, Ladakhi (Bodhi) and Arabic (Nasq). Pakistan has a long-standing policy of imposing Urdu while suppressing vernaculars. This stems from the language ideology that Urdu alone is the language of the Muslims of the subcontinent. The language policy of the Jammu and Kashmir government seems to be no different.

It is busy suppressing the use of the mother tongue in Kargil district. Clever political steps are being taken to extend Kashmiri political hegemony over Kargil. The result would be a separation of Kargil from Ladakh, where lie its racial and linguistic roots. Kargil people would eventually lose their language. It is time to expose this policy of stealth to snatch Kargil from Ladakh aimed at joining it to Kashmir. The mainstream political parties of J & K have been stealthily playing a linguistic card and altering names of geographical entities.

In contrast, our all India parties of all hues seem to be blissfully unaware of what is going on. The LAHDC-for-Kargil has been allowed to function for over a decade, although its legal validity is patently questionable (The act passed in the assembly provides for a single Council, whereas now two independent Councils are functioning).

In view of the three developments in the geopolitical situation mentioned above, India should call for the return of Gilgit-Baltistan with greater vigour. It should be noted that the language factor which was instrumental in the secession of Bangladesh is also present in Baltistan, albeit in a nascent way.

The least that India can do is to encourage the poorly funded and struggling activists of the mother-tongue movement in Kargil; this would automatically boost the morale of the language activists of Baltistan. Kashmiri unionists (as opposed to separatists) should take a leaf out of recent literary development in Baltistan and cultivate their own culture and language.

References:

Kazmi, S. M. A. (1996) “The Balti Language”, Chapter in ‘Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh: Linguistic Predicament’, Edited by P.N. Pusp and K. Warikoo, Himalayan Research and cultural Foundation, Har Anand Publications.

Gupta, Radhika (2012) “The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil,” Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for

Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/13

Courtesy: NewsBharati