By Swapan Dasgupta

Offensive or even ‘blasphemous’ postings on social media is a familiar problem the world over. India too has had its share of posts that are calculated to offend, anger and disgust. However, when a Facebook post of an unknown 17-year-old boy provokes a bout of vicious rioting, it becomes necessary to look beyond the social media.

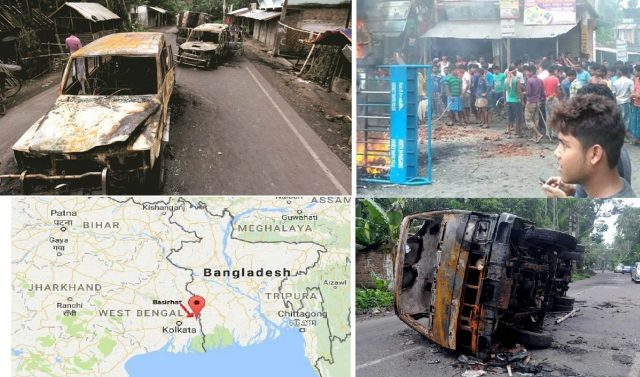

The full extent of the three days of rioting in the North 24 Parganas district of West Bengal, bordering Bangladesh, is still not known to the outside world thanks to some draconian information management by the State Government. However, from the available details it is possible to piece together the sequence of events.

First, the reaction to the offensive Facebook post led to some localised Muslim protests. Secondly, without any other provocation, this protest escalated into a wave of rioting — particularly in Basirhat town — that targeted homes and shops belonging to Hindus. Among the places vandalised were Hindu temples. That most of the local Hindus belong to OBC and Dalit communities is a detail that can be kept at the back of our minds. There was apparently no police response to the mob vandalism. Thirdly, the following morning a MLA belonging to the Trinamool Congress (TMC), directed the police into arresting some 15 men who happened to be all Hindus. There is no report of any similar action against the ringleaders of the mob violence against Hindu homes. These arrests triggered a wave of counter-mobilisation by the Hindus. The violence had by then spread beyond Basirhat to neighbouring areas and resulted in the death of a man who was said to be a RSS worker. Fourthly, the escalation and spread of communal tension prompted the administration to order more stringent policing and withdraw the TMC MLA from local political management. The situation was brought under control by the police while the blame game was played on TV channels.

On the face of it, and going by the version being put out by the TMC, the disturbances were unfortunate but not extraordinary. Indeed, the incident fits quite easily into the larger narrative of localised, small-scale tensions that will soon be forgotten and won’t acquire the notoriety of the riots of, say, Gujarat 2002, Mumbai 1993 or even Muzaffarnagar 2013. After all, only one person died in the disturbances.

It is likely that this attempt to underplay the disturbances will also be coupled by an attempt to blame the whole thing on the BJP and other Hindu organisations. It will also be linked to the attempt of the BJP to enlarge its footprint in West Bengal, as part of its eastern expansion programme. Some of the more ‘secular’ newspapers from Kolkata have already done so.

This denial and attempt to link the communal disturbance to electoral politics are likely to be self-defeating. For a start, the Basirhat riot is not a freak disturbance that is an aberration in a golden Bengal marked by peace and brotherhood of all communities. For the past five years or so, communal faultiness have reappeared in Bengal. There have been minor riots and hundreds of smaller incidents that have systematically vitiated the environment. The reasons have as much to do with both reality and, more important, perceptions.

To begin with, there is a growing perception among those Bengalis who identify themselves as Hindus that Mamata Banerjee has become a captive to her Muslim vote bank. This perception is roughly equivalent to that which formed around the previous Congress Government in Assam or the Muslim-Yadav tag which was a feature of the erstwhile Akhilesh Yadav administration in Uttar Pradesh. Much of this perception is a consequence of symbolism. The ban (later lifted by the courts) on Durga Puja immersions on Vijayadashami last year, the ban on Saraswati Puja in some schools this year, the appointment of a Muslim minister to head the Tarakeshwar Development Board this year and the subtle, State-approved de-Hinduisation of Bangla are just some of the issues that have begun rankling. Add to this the licence given to radical Muslim preachers and the kid glove treatment of minority criminality and it is possible to understand why communal tension in Bengal is increasing.

What is a new development is the fact that increasingly the Hindu backlash to some of these excesses is acquiring an organised character. Whether this is due to the larger Hindu consolidation in the country or owes to the aggressive mobilisation by groups such as Hindu Samhati is worth exploring. However, the net result of this sudden Hindu counter-assertiveness fuelled by a sense of victimhood is triggering localised resistance. Political rivalry in West Bengal, ever since the 1970s, has been less than gentlemanly and is laced with violence in the localities. The communal tension has been grafted on to that unfortunate inheritance.

For Mamata Banerjee, the pro-Muslim tilt is not born of conviction but is an opportunistic response to the fact that en bloc Muslim support is a sure shot election winner. However, the emerging Hindu consolidation is complicating matters and creating divisions in the ranks of the TMC’s non-Muslim support base. The BJP has partly succeeded in ousting the Left as the main opposition. But it is still a poor number two. It will remain that way as long as it is unable to combine its personification of Hindu nationalism with a more evolved approach to the other development issues confronting West Bengal. Indeed, it may be left high and dry if Mamata makes her approach to communal issues more even handed.

Courtesy: The Pioneer