The theory that India got rid of the British solely through non-violence needs a revisit. A balanced view of the freedom struggle that acknowledges the role of armed struggle is needed

The theory that India got rid of the British solely through non-violence has been epitomised by the song, ‘De di haemin azadi bina kharag bina dhaal’. After exercising its mythical sway over Indian psyche, it has begun wilting in the heat of facts and arguments as emerged in recent years. An alternative strand of freedom movement that relied on the armed struggle has begun to receive its fair share of attention.

Long legacy of armed struggle: It constituted a long legacy, starting with the Chapekar Brothers and included martyrs with stellar gallantry as Khudiram Bose, Bagha Jatin, Chandra Shekhar Azad, Bhagat Singh, Benoy-Badal-Dinesh, Surya Sen to name a few. Organisations like the Anushilan Samiti, Jugantar, the Ghadar Party and the Indian Independence League (IIL) carried out the struggle in India and abroad.

Proponents of the ‘alternative strand’ claim that the long chain of armed struggle eventually culminated in the formation of the IIL, which in-turn led to the formation of the Provisional Government Of Free India (PGFI) in East Asia. Notably, former leaders of the Anushilan Samiti and the Ghadar Party played key roles in starting the IIL. Subhas Chandra Bose infused a new life into it to launch the armed war of liberation against the British.

Two contrasting ideologies: How effective were these two ideologies? What eventually caused the unseemly hurry for the crown to leave India? Which of the two caused it? Further, was the credit due to ‘one’ hijacked by the other? Answering these requires a juxtaposition of mass movements convened by Gandhi-led Congress with the PGFI and its struggle through the Indian National Army.

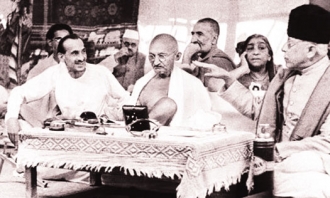

Under the leadership of the Mahatma, the tallest Indian leader, the Congress played a very important role in awakening the masses to the cause of freedom. However, to be truthful to facts, all three mass movements launched by the party viz, non co-operation movement (1921-22), civil disobedience movement (1930-33) and quit India movement (1942) failed to achieve their professed goals.

Great mass movements by the Congress but Swaraj remained elusive: The non co-operation movement was coupled with the Khilafat movement. BR Ambedkar observed that the movement’s primary object was Khilafat and Swaraj was added as a secondary object. Many raised questions about the ethical aspect of this coupling. But the Mahatma succeeded in carrying the Congress with him in support of the Khilafat cause.

He held out the hope of ‘Swaraj within a year’. Indians in general were enthused by the dream, while many Muslims, including the Moplahs of Kerala, thought it as a path to set up Khilafat kingdom in India. This dichotomy frustrated the twin goals of both Khilafat and Swaraj. Notably, Khilafat led to the blood-curling massacre of the Hindus by Moplahs in Kerala in 1921.

Having looked the other way on the Mopla massacre, the Congress suspended the movement abruptly on February 1922 in the wake of Chauri Chaura, a lone incident of violence. The movement fizzled out pushing India to despair; brought Hindu-Muslim relations to a nadir; and made little progress towards Swaraj.

The 1928-29 Calcutta session was the stepping stone to the Civil Disobedience movement launched in 1930. The Congress had demanded both ‘dominion status’ and ‘adoption of constitution framed by Motilal Committee’ and gave a year’s time to the Government to accede. Being rebuffed by Government apathy, the party set Purna Swaraj as its goal at the 1929-30 Lahore session. In February 1930, the All India Congress Committee resolved to begin civil disobedience to achieve it.

The programme got a head start with the Mahatma’s Dandi March and spread like wild fire. Government repression ended up adding to its intensity. While mass participation were soaring, Gandhiji inexplicably fell into British trap, suspended the movement, attended round table conference (1931) and brought simmering religious and caste-based divisions in the Indian society into open.

His attempt to revive the movement upon return to India from the round table conference in January 1932 was brutally suppressed by the Government, prompting him to suspend it in May 1933. For all practical purposes, the movement culminated with no progress towards Purna Swaraj. Motilal Nehru’s constitution was forgotten, India’s native political divisions became pronounced and Gandhiji resigned from the Congress in October 1934, to devote to nation-building activities.

Quit India movement (1942) was prima facie ill-timed and poorly planned. As was rightly prophesied by Rajagopalachari, the entire top leadership of the Congress, including the Mahatma, was promptly put behind the bar. Sporadic mass upsurges followed, but they were brutally suppressed. Bulk of Congress leadership languished in jail till June 1945. Muhammad Ali Jinnah led Muslim League exploited the vacuum to the hilt and communalised the sub-continent.

While making little impact on the British, the movement facilitated the rise of the Muslim League, and strengthened the demand for Pakistan and communalisation of the entire country. Thus at the end of the three great movements, the Congress was virtually emaciated and India remained very far from ‘independence’.

Provisional Government of Free India and the last war of independence: When gloom and despair enveloped India in 1943, the PGFI-led by Bose galvanised nearly three million strong Indian expatriates in East and Southeast Asia and raised the strength of the Indian National Army to nearly half a lakh soldiers preparing to launch an armed war of liberation. At least eight countries, including two major axis powers viz, Germany and Japan, recognised PGFI as the Government of India.

In that momentous month of October 1943, PGFI was set up on the 21st, and it declared war on Britain and America soon thereafter. Though militarily defeated, Indian National Army soldiers displayed exceptional spirit and patriotism in their war against the British in India’s eastern hills and inside Burma. But their indomitable courage to challenge the might of the British brought a subterranean change in the psyche of the enslaved nation. This came in full public view during the ensuing Indian National Army trials.

The ideological conquest — Indian National Army phobia overwhelms the British: Even before the Indian National Army trials began in India, Viceroy Wavell was deeply anxious of the growing appeal of Bose and Indian National Army on the Indian Army. To the Secretary of State (SoS) he wrote, “This is the first occasion on which an anti-British politician has acquired a hold over a substantial number of men in the Indian Army and the consequences are quite incalculable.”

The trials had set India aflame. Governors of Punjab, Central Provinces and Berar, North-West Frontier Province amongst others, all expressed concerns on the growing support for the Indian National Army. Auchinleck, the CIC, cautioned his chiefs of staff against the vigorous and continued Congress propaganda extolling the Indian National Army as true patriots and condemning the Government which could gravely deteriorate the morale of the Indian members of the Armed Forces and even mutiny by some units.

Eventually, he had to remit the sentences of ‘transportation for life’ for top three Indian National Army commanders apprehending that any attempt to impose them would lead to chaos in the country at large and probably to dissensions and mutiny in the Army culminating in its dissolution…’ The remission of sentences of top three Indian National Army leaders did not douse the fire. In a couple of months, a serious revolt broke out in the Royal Indian Navy and raged for nearly a week. It was clear that the Indian National Army’s spirit had begun to erode the loyalty of the British Indian Armed Forces and the process was irreversible!

It appeared what none of the earlier movements could do, the Indian National Army had done — and the Congress was expedient to leverage it, even if its ideological commitments were to be renounced. A nervous Wavell wrote to the SoS, complaining that top Congress leaders were making statements to provoke mass disorder. They were glorifying the Indian National Army, asserting that the British could be turned out of India in a short time and threatened that the officials responsible for suppressing the 1942 movement would be tried as war criminals and punished.

Ideological shift in Congress: At that juncture, the role played by the Congress in ideological terms became a vital question to the crown. From a party which had opposed armed struggle for freedom, did not seek India’s independence out of Britain’s ruins, believed in the policy and practice of non-violence in the struggle for attaining swaraj and had deep-seated allergy to Bose’s plan of armed struggle, Britain expected support and solidarity. She was stunned by this unexpected ideological somersault.

Time to acknowledge, even if late: In the circumstances, Britain genuinely wanted to cut its losses. After having set the deadline to leave India by June 1948, it advanced its withdrawal to August 1947. That speaks volumes. It also reopens the question of whether India achieved freedom solely through non-violence and points at the necessity of re-appraisal of the contribution of PGFI and the Indian National Congress. Seventy four years ago, on October 24, 1943, the PGFI had declared war on Britain and the US. This was the last war of Indian independence. As a self respecting nation, this glorious chapter of our history should be revisited at least now and a more balanced view of freedom struggle must be attained.

– Sudip Kar Purkayastha

(The writer is a columnist and an author)

Courtesy: The Pioneer