In John Le Carre’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, a sombre George Smiley asked Bill Haydon, a former colleague at MI6 why he betrayed his country and became a Soviet mole. “It was,” Haydon replied unhesitatingly, “an aesthetic choice as much as a moral one. The West has become so ugly.”

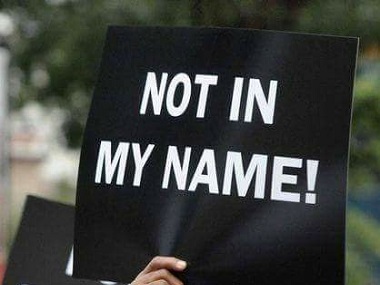

In the end, most of life’s choices are aesthetic, whether we call it so or prefer the label ‘lifestyle’. The thousand or so individuals — educated, articulate, aware and well-off — who assembled in various cities last Wednesday evening determinedly flaunting ‘Not In My Name’ placards were convinced they were there with a mission: to rescue India from ugliness.

Their concern was understandable. The past week witnessed an ugly incident that led to a young Muslim boy being subjected to a murderous assault in a commuter train in Haryana. Clearly the boy was picked on, not merely because a gang of bullies was in search of targets but because he was visibly a Muslim. It was, without any doubt, a hate crime.

There is a streak of underlying violence in India’s public culture. It has always existed and politics has often fuelled it. The 1857 revolt was horribly brutal, as was the repression that followed its defeat. Mahatma Gandhi bravely tried to reinvent this bloody inheritance and surprised the world with his success. After Independence, political violence has been supplemented by flashes of mob violence aimed at either settling scores or securing justice. From robbers who have been routinely lynched, suspected witches bludgeoned to death and road rage expressed through knife and gun attacks, India remains a violent place, made even more so by the callousness and ineptitude of law-enforcing agencies. Sadly, human life is very cheap in India.

Undeniably, the grisly lynching in a train could have been averted had the railway police been alert and fellow passengers shown better sense. The incident points to weaknesses in state institutions and the shortcomings of our civic culture. These issues should concern both the political class and citizens. To that extent, the outrage over the incident is heartening and exemplary action could even serve as a future deterrent.

However, at last Wednesday’s protests people came with a baggage that could prove self-defeating for the larger cause of amity and justice.

For a start, the protests were marked by selective indignation. Although the killing in Haryana had no hint of politics — and although it revealed popular mentalities — it was used to suggest that somehow the Modi government created the environment of anti-Muslim hysteria. The beef controversy was repeatedly invoked.

Yet, there was a studied silence on the lynching, the very same day, of a policeman (also a Muslim) in Srinagar by separatists milling outside a mosque. The failure of the protest organisers to put the Haryana and Kashmir killings on par revealed a clear and deliberate agenda: to kick Modi and brush aside related issues that didn’t quite fit the narrative of Hindu self-flagellation.

Secondly, the protests were tinged with a generous measure of social condescension that was apparent from the chatter on social media. It is one thing to extend the outrage to cow protection vigilantism — an ugly phenomenon that invited harsh comments by Modi —but the real irritation seemed to be over the denial of food freedom. What the protesters seemed unwilling to grasp was that — some states of India apart — the prohibition on beef carries a large measure of social sanction.

The attempted use of the Constitution to facilitate a more permissive policy on beef seemed an affront to common decencies and made the protests seem an extravagant display of rootless cosmopolitanism.

To develop a critique of the Modi government is legitimate. However, this exercise has degenerated into a show of social disdain for both Modi and the ‘Hindu’ trappings of the BJP. The more the liberal brigade paints Modi and his ‘bhakts’ as crude, neo-literate, insular vegetarians preoccupied with Ram, Hanuman and gau mata, the more will be its disconnect from a popular culture firmly centred on Hindu symbolism.

In the past three years there has been a shift in social and political attitudes: the killing of an innocent Muslim boy by a mob remains as unacceptable today as it was yesterday, but the ban on cow slaughter has become non-negotiable and no longer subject to the pulls of ‘modernity’. Equating the more evolved sense of rootedness with a corresponding loss of humanity is a wrong number.

India may be imperfect, but it isn’t so ugly as to warrant emotional treachery.

By Swapan Dasgupta

Courtesy: Times of India