-Dr. Shreerang Godbole

As India enters the 75th year of her freedom, it is time to recall events and examine narratives related to our Freedom Movement. Close on the heels of this momentous occasion comes the centenary of the Rashtriya Swayamasevak Sangh or the RSS (hereafter Sangh). A question that is often asked – what role did the Sangh play in our Freedom Movement? This series of articles aims to examine the role of the Sangh in the Civil Disobedience Movement (popularly called Salt Satyagraha) of 1930. We shall lean heavily on original documents in the Sangh archives as also on contemporary Marathi newspapers such as the Kesari and Maharashtra biweeklies that were published from Pune and Nagpur respectively.

Sangh and Sangh Swayamsevaks

To the general question – what role did the Sangh play in our Freedom Movement, the answer is pretty straight forward. The role of the Sangh is virtually zero but the role of Sangh swayamsevaks is certainly significant. Lest this statement cause misconceptions, let us examine the thinking of the Sangh’s founder and maker Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar. This thinking determines Sangh policy to this day.

At a time when the question on everyone’s mind was ‘When and how shall we get freedom’, Dr. Hedgewar asked himself, ‘Why did we lose our freedom and how should preserve it?’ Not only did Hedgewar contemplate on this moot question, he devised and started a framework to rid society of those shortcomings which in his view led to slavery. The task of nation-building that he embarked on was long-term. In contrast, agitations by their very nature have short-term objectives.

Maintaining a judicious balance between contemporary agitations and the abiding task of nation-building can be challenging. The ingenious Hedgewar met this challenge by insulating his nascent organization from the rough and tumble of agitations but allowing Sangh swayamsevaks to participate in them. As was his wont, Hedgewar led by example. He himself participated in such agitations but kept the Sangh aloof from them. Hedgewar conceived of a society wherein the need for such agitations would not be arise. He had certainly not conceived the Sangh as a firefighting entity that would content itself by rush to the aid of a weak society on an ad hoc basis. He sought to increase the innate strength of Hindu society such that the Sangh itself would be rendered superfluous.

Another fundamental thought was uppermost in Hedgewar’s mind. He abhorred even a hint of duality between the Sangh and the wider Hindu society. He had not started the Sangh on the lines of the Arya Samaj or Ramkrishna Mission as separate organizations within Hindu society. Hedgewar looked upon the Sangh as an organization of Hindu society, not within Hindu society. This distinction is borne out by at least two incidents in Hedgewar’s life.

In 1938, a Civil Resistance Movement was started in protest against the Nizam’s atrocities on Hindus in Hyderabad State. Hedgewar’s refusal to give directives to Sangh shakhas (lit.branches) to participate in the Movement attracted criticism from pro-Hindu quarters. However, Hedgewar made it a point to write congratulatory letters to those who participated in the Movement. His refrain was, “The Sangh swayamsevak is a member of Hindu society. He does not resign from this membership when he joins the Sangh. As such, he is free to do whatever is required of him during such agitations as is the case with each member of Hindu society” (Sangh archives, Hedgewar papers, registers\Register 1 DSC_0056).

Though the Sangh remained organizationally aloof from this Movement, Hedgewar took care to ensure that adequate number of resistors participated in it. Shankar Ramchandra Date, a Secretary of the Maharashtra Provincial Hindu Sabha was closely associated with this Movement from its inception. In May 1938, Hedgewar was in Pune to preside over a Hindu Youth Conference. Date met Hedgewar and impressed upon the latter the need to raise at least 500 resistors. Hedgewar assured Date, “You need 500 people to participate in the Satyagraha, is that all? Do not worry. You take care of other logistics.” The confidence and empathy with which Hedgewar uttered these words left a lasting impression on Date’s mind (Sangh archives, Hedgewar papers, Dr Hedgewar Athavani 2 0001-A to 0001-D).

Hedgewar was confident that even though the Sangh as such remained passive, Sangh swayamsevaks who had received their lessons in patriotism in Sangh shakhas would dissolve their organizational identity and spontaneously take part in any movement that was in national interest.

Hedgewar’s confidence was not misplaced. Several office-bearers and swayamsevaks of the Sangh took part in the Movement as ordinary Hindus. To give direction to the Movement in Satara district and Princely States in Southern Maharashtra, a War Council was constituted in February 1939. Its President was none other than the Sanghachalak of Satara District Shivram Vishnu Modak. Another member of the War Council was Kashinath Bhaskar Limaye who was Maharashtra Provincial Sanghachalak (Kesari, 17 February 1939). A huge rally was held on 22 April, 1939 at Pune’s Shaniwar Wada grounds to see off a contingent of 200 resistors who were to depart the next day under the leadership of Hindu Mahasabha leader L.B. Bhopatkar. Hedgewar was on the dais (Kesari, 24 April 1939). The next day, Hedgewar went to the Railway Station to personally see off these resistors. Hundreds of Sangh swayamsevaks took part in the Civil Resistance Movement in their personal capacity. Among them was Hedgewar’s nephew Waman. Waman was confined to a dark cell for four days and severely thrashed by the Nizam’s Police (Kesari, 9 June 1939).

In April 1939, the District Magistrate of Pune passed an order prohibiting playing of musical instruments in front the Sonya Maruti Temple on the pretext that it disturbed the namaz at the nearby Tamboli Mosque. Hindus in Pune launched a satyagraha in protest. Hedgewar happened to arrive in Pune at the time. Some people asked Hedgewar, “What will the Sangh do in this satyagraha?” Hedgewar jocularly replied, “This satyagraha is for all citizens. So, hundreds of Sangh swayamsevaks will take part as citizens. But, if it necessary that they be identified separately, I shall place a pair of horns on each one’s head.”

Hedgewar had recently bought a pair of bison horns to hang on the wall of his Nagpur residence. That reference found mention in his reply! (Sangh archives, Hedgewar papers, Nana Palkar\Hedgewar notes – 5, 5_141). It is noteworthy that Hedgewar himself took part in the satyagraha and courted symbolic arrest. Yet, he steadfastly refused to involve the Sangh as an organization.

One significant exception to Hedgewar’s general rule exists. In December 1929, the Lahore Session of the Indian National Congress adopted the goal of Purna Swaraj or Complete Independence and called for 26 January 1930 to be observed as Purna Swaraj Day. Hitherto, the Congress had Dominion Status as its goal. Hedgewar who had always been an ardent supporter of Complete Independence was overjoyed. In a directive to all Sangh shakhas dated 21 January 1930, Hedgewar wrote, “On 26/1/1930, all shakhas of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh should hold meetings of all swayamsevaks of their respective shakhas at their respective Sanghasthans (lit.assembly place of the Sangh) and salute the national flag, explain through lectures what is freedom and how it is the duty of every Indian to keep this objective before oneself and conclude the programme by congratulating the Congress for championing the goal of Independence” (Sangh archives, Hedgewar papers, A Patrak by Dr. Hedgewar to the swayamsevak – 21 Jan 1930).

If one were to grasp Hedgewar’s thinking, the question of what the Sangh did in the Freedom Movement becomes redundant. Let us now turn to the Jangal Satyagraha

Civil Disobedience Movement

The nature of a future Constitution of India ought to have been discussed by a Convention Parliament or a Round Table Conference. Instead, the British Government announced the constitution of Simon Commission on 8 November 1927 to prepare the future Constitution of India. This Commission that did not have a single Indian as its member was opposed by all Indians, irrespective of party affiliations. Against this background, the All-Parties Conference, which met at Lucknow from 28 to 31 August 1928, unanimously accepted the Constitution drafted by the Motilal Nehru Committee appointed by it. However, when no guarantee of immediate Dominion Status was forthcoming from the British, the Congress in its Lahore session (December 1929) resolved a “complete boycott of the Central and Provincial Legislatures and Committees constituted by the Government” and authorized the “All-India Congress Committee, whenever it deemed fit, to launch upon a programme of Civil Disobedience, including non-payment of taxes” (p 326). The Purna Swaraj resolution at the Lahore Congress also stated, “India has been ruined economically. The revenue derived from our people is out of all proportion to our income. Our average income is seven pice (less than two-pence) per day, and of the heavy taxes we pay, 20 per cent, are raised from the land revenue derived from the peasantry, and 3 per cent, from the Salt Tax which falls most heavily on the poor” (R.C.Majumdar, History of the Freedom Movement in India Vol 3, Firma KL Mukhopadhyaya, Calcutta, publication date unknown, pp.326, 331).

At its meeting held on 14, 15 February 1930, the Congress Working Committee authorized Gandhi to chalk out the Civil Disobedience Movement. Taking 79 male and female satyagrahis with him, Gandhi completed a slow march over 241 miles in 24 days and reached the sea at Dandi. On 6 April 1930, Gandhi picked up some salt left by the sea waves and broke the Salt Law. This act had a profound appeal across the country. Salt laws were broken in many places, salt was made in pans in the cities, and mass arrests and other repressions followed. Sixty thousand political prisoners were put in jails (Majumdar, pp 334, 338).

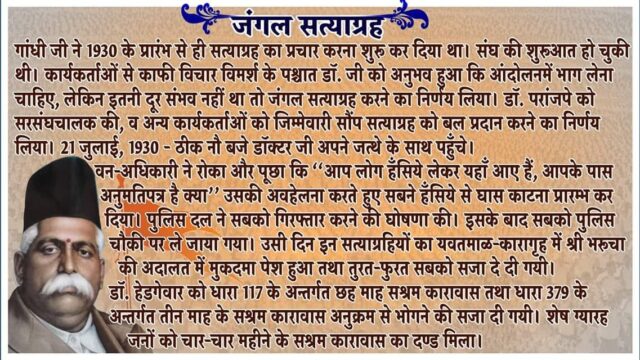

Jangal Satyagraha

The Salt Satyagraha found symbolic and limited resonance in Central Provinces and Berar. The Central provinces consisted of the Marathi-speaking Nagpur division comprising of districts of Nagpur, Wardha, Chanda or present-day Chandrapur and Bhandara. The Hindi-speaking region of Central Provinces had three divisions of Narmada (Nimar, Hoshangabad, Narsimhapur, Betul and Chhindwara districts), Jabalpur (Jabalpur, Sagar, Damoh, Seoni and Mandla districts) and Chattisgarh (Raipur, Bilaspur and Durg districts). The division of Berar (present-day Vidarbha) comprised of Amravati, Yavatmal, Akola and Buldhana districts. This region neither had easy targets as salt works nor a sea shore. As part of the satyagraha, salt was first made on 13 April, 1930 from saline wells in the two villages of Dahihanda (dist. Akola) and Bhamod (dist. Amravati). The Salt Satyagraha in Berar continued till 13 May 1930 (K.K.Chaudhary, ed. Source Material for a History of Freedom Movement, Civil Disobedience Movement, April-September 1930, Vol. XI, Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay, 1990, pp. 873, 921). To circumvent the difficulty in manufacturing salt, provinces such as Central Provinces and Berar targeted other repressive laws.

The Indian Forest Act, 1927 was particularly repressive to farmers in Berar. Hitherto, there was no restriction or tax on timber, other forest-produce and cattle-fodder. This situation changed as the Government imposed control on forests under the guise of expanding and protecting them. Rather than looking after the interests of farmers, the Government sought to fill its coffers. As cutting of grass and pasturing of cattle in forests was prohibited, cattle-fodder became scarce and expensive. Forest officers compounded the situation with their arrogance. Representations to the Government both within the Provincial Council and in public meetings proved to be of no avail. Left with no other option, the Berar War Council which had been formed to oversee the Civil Disobedience Movement in Berar resolved to break the Forest Act by cutting grass without license in a restricted forest. Madhav Shrihari alias Bapuji Aney was to lead the first batch of satyagrahis at Pusad (dist. Yavatmal) on 10 July 1930 (Chaudhary, p. 957).

Political dacoity at Hinganghat

Where was Hedgewar amidst all this tumult? Hedgewar was under British watch right since August 1908. Detectives continued to tail him even after he started the Sangh in 1925. By 1926, Sangh shakhas had started functioning well in Nagpur and Wardha. At this time, a plan was hatched to bring back those revolutionary colleagues of Hedgewar who were originally from Central Provinces but were still stranded in Punjab. This plan to bring back both men and material was hatched by Hedgewar’s colleagues Dattatraya Deshmukh, Abhad and Motiram Shravane and set in motion in 1926-27. Hedgewar’s revolutionary comrade Ganga Prasad Pande was in charge of this operation. After this plan was executed, Pande fell ill and came to Wardha in 1927. A pistol that he had kept for self-protection fell into the hands of his friend. In 1928, an attempt was made to raid the Government treasure-chest at the railway-station in Hinganghat (dist. Wardha). Newspapers reported that a pistol had been used in this attempted political dacoity. Pande knew that the pistol was his and had it retrieved. Realizing that the trail of the pistol would lead to him, Hedgewar and his right-hand Hari Krishna alias Appaji Joshi (Secretary of Central Provinces Congress Committee, Member of All India Congress Committee and Wardha District Sanghachalak) landed at Pande’s place at night. The duo took charge of the pistol. Hedgewar thrashed a waiting detective and the two fled into the darkness.

Henceforth, both Hedgewar and Appaji Joshi were kept under strict surveillance. Not only were their houses watched but their activities in Sangh shakhas and elsewhere were closely watched. People were scared to meet them. In the beginning of 1930, the Deputy Superintendent of Police summoned Appaji. He told Appaji, “Though you are in the Congress, you do not participate in the satyagraha but go to shakhas. You are young and hold radical views. Hedgewar’s leadership is revolutionary. As you are not taking part (in the satyagraha), why should the Government not suspect that you do not believe in non-violence? You have all the material (arms) and we have the information.” Appaji retorted, “If this is true, do you think you will find it by keeping a watch on us? Stop this whole drama that you are staging!”

Appaji’s stance had the desired effect. The surveillance on Hedgewar and Appaji eased. The Court trial related to the Hinganghat political dacoity case got completed and the suspects were handed down punishment. It was imperative for Hedgewar to show the Government that he was no longer a revolutionary. Appaji felt that it was time to draw curtains on the entire episode. In a letter to Hedgewar in February 1930, Appaji wrote that after careful deliberation, he had decided to take part in the satyagraha. To this, Hedgewar replied that he would take a decision after the Sangh’s Officer Training Camp. After the Camp, Appaji again wrote to Hedgewar. Citing Appaji’s health and his own busy schedule, Hedgewar did not immediately give his consent. But when Appaji again wrote to Hedgewar, the latter promptly conveyed his willingness. The two met and finally decided to participate in the satyagraha (Sangh archives, Hedgewar papers, Nana Palkar\Hedgewar notes – 5 5_84-91; as narrated by Appaji Joshi to Hedgewar’s biographer Narayan Hari alias Nana Palkar).

(…..to be continued)

Courtesy : VSK BHARATH